POETS

JAN 10 -31, 2026

Poetry reading and performance dates to be announced.

Featuring work by James Allen, Lucas Dupin, Raheleh Filsoofi, Ryan Habermeyer, Lanecia Rouse, Deb Sokolow, and John Shorb

It cannot be often that a work of art post-dates its title, but if curating is a creative act, this exhibition's title came first. The container of poetry, for this poet, its vessel, should be just that-- an enormous box ship filled to a wobbly, brimming meniscus of 24,000 truck-sized intermodal containers (a technique called containerization). Watch one at sea sometime, you'll never mail a package again.

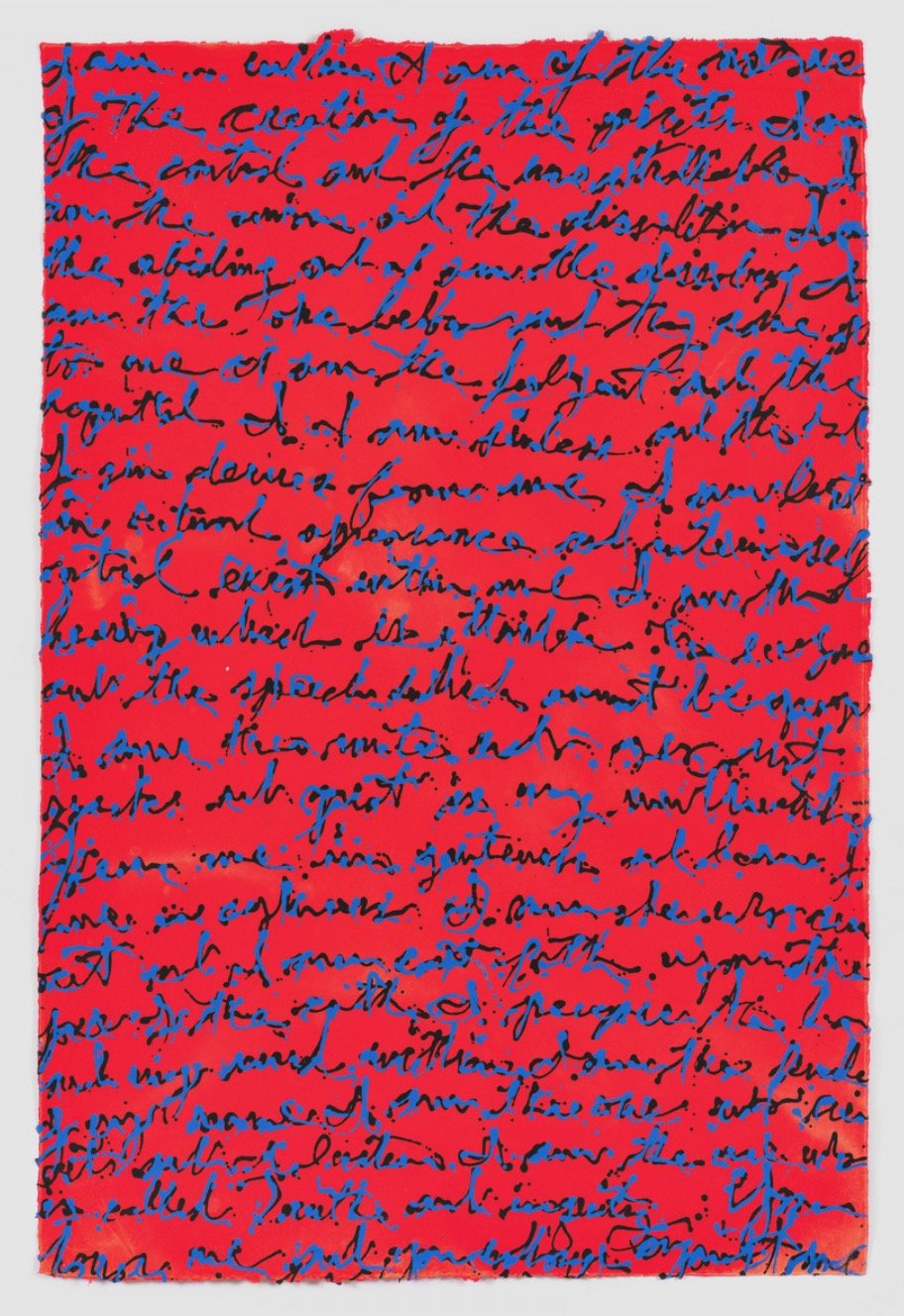

John Shorb

Thom's Letters to Douglas III, 2023

Linen pulp paint on cotton base sheet

60 x 49 in (152.4 x 124.5 cm)

IN10785

Lucas Dupin

Untitled #13 | Bibliomorph Series

Fragments of books, leather on wooden support

29.5 x 31.5 x 2 in (75 x 80 x 5 cm)

IN10787

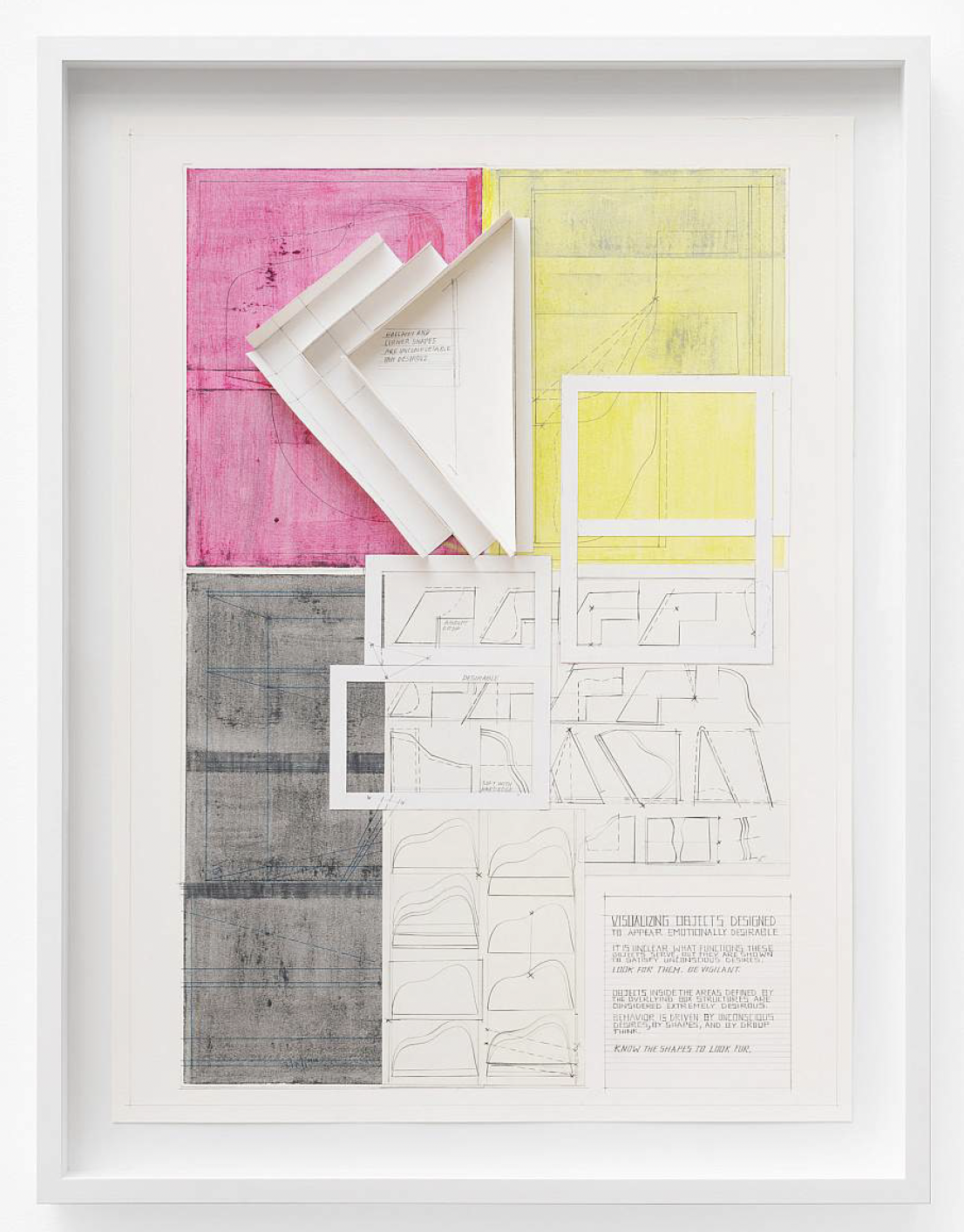

Deb Sokolow

Visualizing Objects Designed to Appear Emotionally Desirable, 2023

Graphite, crayon, colored pencil, ink, and collage on Arches paper

30 x 22 in (76.2 x 55.9 cm)

IN10788

Deb Sokolow Thinking Drawing #1, 2023 Graphite, crayon, colored pencil, pastel, ink, and collage on Montval paper 12 x 16 in (30.5 x 40.6 cm) IN10789

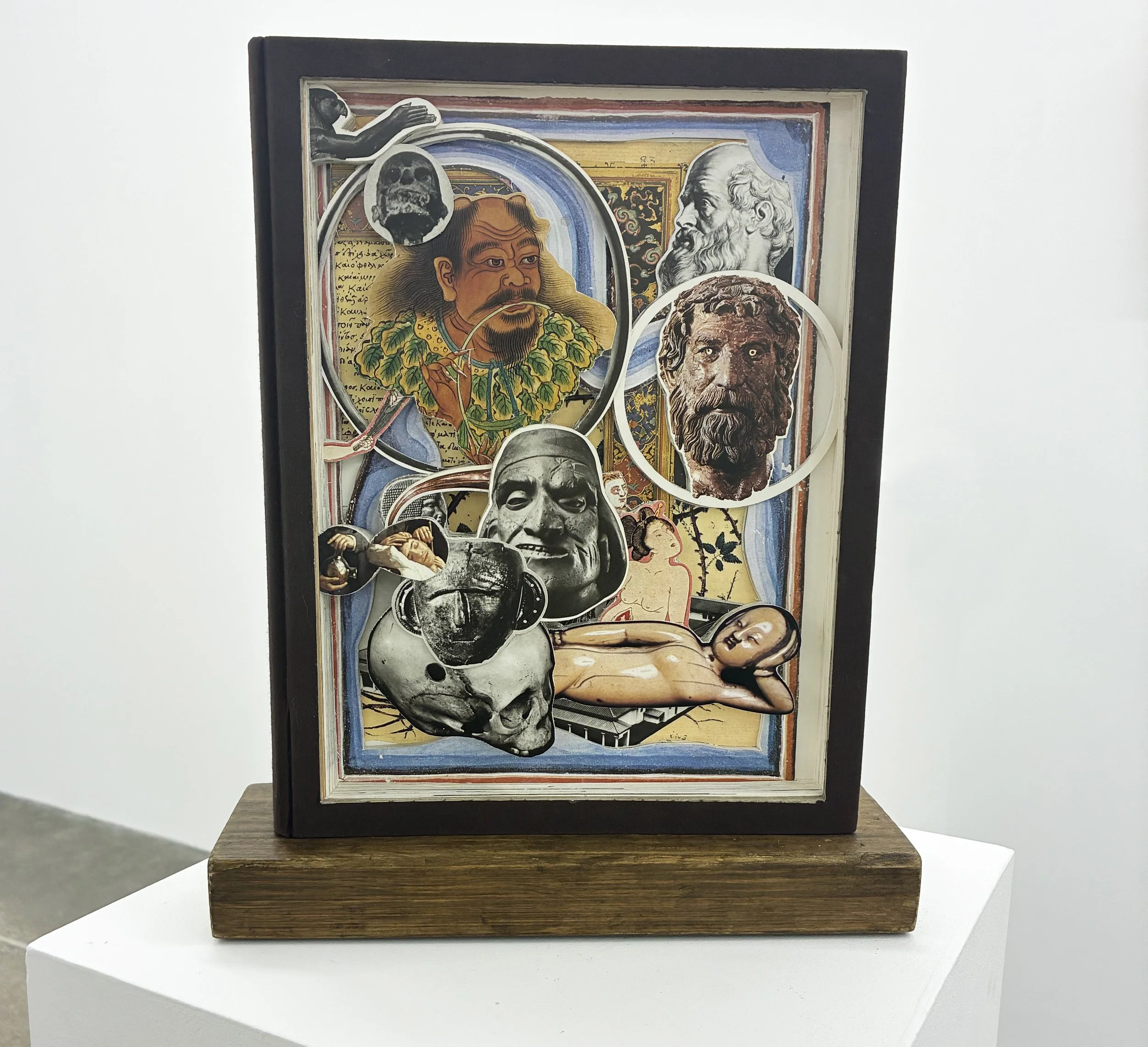

James Allen

Medicine An Illustrated History, 2025

Book excavation

Not that poetry should be dangerous. Most dangerous poetry is forgotten the moment safety reappears on the equally unsteady horizon. No. Poetry should be in the trees where it belongs, but it should also be where it has no earthly business. In better advertising and movie reviews, better packaging and press releases, on toddler's tongues and downtown digital billboards. Which is not to ask for a new slang, or populist jingoisms, but instead better words put to better use. One day there will be an exhibition called SEVEN ARCHITECTS. It will be all about sight lines and the math. My uncle was an architect. He dissuaded me from pursuing the vocation, which I thought would be nifty, spending most of my 9 year old time drawing imaginary buildings on fire with industry. Never build a building til you're 50 what kind of life is that?

Somebody once said poetry is a young man's game, what reads so hideously hollow nowadays in so many ways was also always patently untrue. Careworn, grandmotherly architects can be poets as well as Christopher Smart's cat. My seven year old daughter makes Sylvia Plath look like a Brownie Scout. Sylvia Plath was never a young man for that matter. Nor was Lorinne Neidecker. None of the Great American (men) Poets were ever young men either, rather smoking pipes through early beards as soon as they were hormonally able. Those were my heroes! What is it with poets anyway?

None of the seven artists herein would claim to be poets.

Ryan Habermeyer is a writer of some renown and a thesis could be conceived in favor of labeling what he writes poetry but the man himself does not claim it as such. I'm a poet, and I do, so there.

And Deb Sokolow uses short bursts of insightful language in her drawings in the kind of poetry a Blacklisted Hollywood screenwriter might have written from her prison cell if all she had was a pencil and a (paper) wall.

John Shorb, for his part, manifests a veritable wall of words, be they excerpts from the letters of Thom Gunn or the verses of John Donne, his close-up cropping creates a crude concrete poem of a maestro's handmade scratches. Raheleh Filsoofi's words are made of dirt. Her poetry is music and clay, mixed with her fingers and carved with her breath.

For Lanecia Rouse, the mining of her multi-faceted and vast, universal histories combines as seamlessly as her deft use of collage, sculpture, painting and vernacular photography. Personal artifacts become talismanic votives— for lost ancestors, lost pasts and the joy in their rediscovery.

Brazilian Lucas Dupin builds architecture that rises through walls and sculpts landscapes that drip from hooks, all consisting of chains of tiny, interlinked book spines. His poems are unreadable, but the viewer can inhabit them.

What Dupin does to spines, James Allen maneuvers through each page of his library. His deft excavations treat each page as a blueprint for the one before it as much as the page after. He weaves an epic poetry that contains histories, each of which can be visible at a glance, without reading a single word.

Venezuelan Miguel Braceli’s slingshot harnesses all the power and glory of language; weaponizing the dictionary (or bible, for poets there’s little difference) in its perpetually pregnant state— a missile silo sporting an open hatch. Perceptual tension and conceptual precepts force the viewer to confront the consequence of words with medieval technology at the service of contemporary mores— a tour de force one liner.